When simply bending forward ends in pain

By Peter Georgilopoulos, APA Sports Physiotherapist, Spine + Body Gold Coast.

You were moving well without pain although typically there were occasional bouts of morning stiffness which generally resolved after a few minutes of walking and general movement. Then the unforeseeable happened, based on the most innocuous and insignificant movement. You may have lifted a (not so heavy) weight, bent forward to tie your shoelaces, reached for something under the bed or reached into the back seat of your car for your briefcase.

Suddenly you are gripped by severe pain in your back (and possibly either buttock or leg) compounded by an immobilising spasm in the muscles on either side of your midriff. Any attempt to bend forward elicits severe pain and quite possibly a deep throbbing nerve pain into your posterior thigh, groin or calf. Those coming to your aid can do little to help you ease your symptoms as you struggle to find any position of comfort. Sitting certainly doesn’t feel like it’s the right thing to do and standing up straight is virtually impossible. Worse still, looking at your reflection in a mirror you see that your pelvis has shifted to one side severely and any attempt to straighten up is met with severe jabs of pain.

Those that have experienced this scenario (and statistics indicate that 80% of the population will do so at some point in life) may wonder if they will ever enjoy undisturbed sleep again or be able to return to work or sport.

So, what has happened?

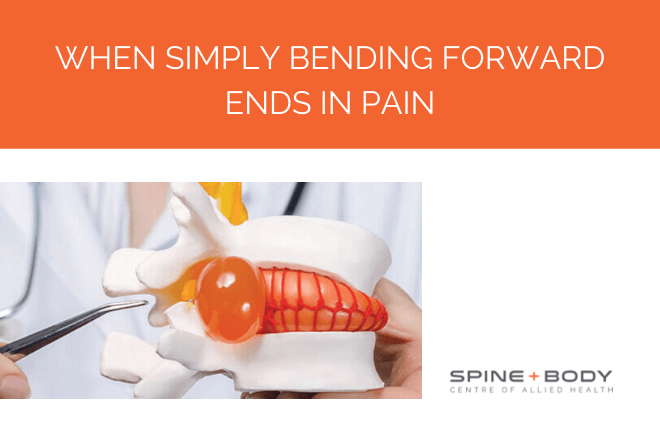

What is described here is a typical disc prolapse (aka disc herniation, disc bulge or, incorrectly, a “slipped disc”). The discs function as shock absorbers between each of the independently moving bony vertebrae with the exception of the sacrum [tailbone] located within the pelvic rim which is fused. The discs consist of a ligamentous outer wall and a gelatinous core. As there is no bony or calcific structure within the disc, it cannot be viewed on X-ray so the only diagnostic investigations that are useful in detecting disc pathology are MRI, CT or PET scans.

Think of the disc as a car tyre lying on its side- it has a firm but flexible outer wall and a compressible inner structure. If we could compress the side- lying tyre from above and below, the rubber outer wall will expand equally and symmetrically according to the amount of pressure applied and rebound back once the pressure is removed.

On bending forward however, the dynamics within the disc alter significantly. The pressure at the front portion of the disc increases as the vertebrae are squeezed closer together and pressure is reduced at the back portion of the disc as the space widens. This forces the gelatinous disc nucleus to the back of the disc just like a tube of tooth paste is squeezed from one end to the other thereby placing increased pressure on the back of the disc wall. Under normal circumstances the posterior disc wall can easily withstand this increase in pressure but in cases of severe load such as lifting an excessively heavy item, or through combined bending forward and rotation (made worse by attempting to lift a weight from this position), the force may exceed the outer wall’s ability to withstand the pressure. The excessive force may distend and even tear the outer wall allowing the nuclear centre to extrude outwards.

This causes immediate and severe pain and In the event that this bulge touches or compresses any adjoining nerve, pain can radiate along the length and distribution of that nerve. Pain can generally radiate from the buttock to the posterior thigh and may even extend to the level of the foreleg or foot. Commonly protective muscle spasm is elicited spontaneously further compounding the inability to move. Symptoms may include a “burning “sensation [ causalgic pain ], numbness [anaesthesia ] or pins and needles [ paraesthesia ] depending on how much of the nerve fibre is being irritated . In the worse- case scenario, all these symptoms can co- exist simultaneously and the pelvis may deviate towards the painful side (pelvic shunt) as a means of alleviating pain.

Any attempt to bend forward, to lift a weight or to cough or sneeze causes an immediate exacerbation with the only relief generally afforded when lying on the side. Theoretically, if bending forward exacerbates disc pain, arching backwards should alleviate symptoms by mechanically reducing the disc bulge. For the most part this is true except where the size of the prolapse is so large as to make both bending forward and arching backwards difficult. Typically, there is severe apprehension when attempting to bend forward and patients tend to “walk” their hands back up their thighs to an upright posture.

So how can we manage this? The primary objective is to place the patient on the non- painful side with the knees slightly bent to alleviate muscle spasm and pain. Once settled, attempt to roll onto the back and with knees bent and feet of the bed and gently roll both knees away from the symptomatic side. Perform slowly and avoid pain as this elicits further protective muscle spasm. Hold for a few minutes and gradually attempt to roll onto the abdomen. Gently try to lift the upper body back and prop onto the elbows if possible. If and when possible, attempt to push up onto fully extended elbows arching backwards. Avoid pain and hold for a few minutes. Gently return to side lying and wait a few minutes before attempting to stand. If possible, attempt to weight bear and only sit on a high, firm backed chair preferably with a rolled towel supporting the lumbar curve. DO NOT attempt to bend forward. Seek immediate treatment from a qualified manual therapist such as a physiotherapist.

Even once the symptoms settle, avoid any bending forward for at least two weeks allowing the outer wall to start repairing with scar tissue. Short of two weeks, the disc is highly unstable and may relapse on any forward bending, lifting a weight, attempting sit-ups or crunches or even sneezing when unprepared (ie standing and contracting the abdominals).

When treated appropriately, most disc prolapses repair sufficiently well so as not to cause future eruptions. Of course it is important to maintain spinal mobility, core strength and to always engage correct lifting techniques using bent knees and a straight back.

Book your appointment with Peter Georgilopoulos at Spine + Body.

Peter is Director and Founder of Spine + Body Centre of Allied Health on the Gold Coast ph: 07 5531 6422 or contact us by email here.